We Endorsed A NIMBY.

What to do when politicians go rogue.

What happens when a politician that you’ve endorsed becomes an opponent? I’m not talking about cases of an elected official underperforming or just being a warm body. But as an organization that makes hundreds of candidate endorsements a year, every once in a while it goes extremely poorly.

I’m talking, of course, about Aisha Wahab, the California state senator elected in 2022 with the endorsement of groups like East Bay YIMBY (a YIMBY Action Chapter), East Bay for Everyone, and prominent YIMBY elected officials, including Senator Scott Wiener.

Since then, Senator Wahab has, shall we say, pivoted away from her campaign commitment to “pass laws to ensure we make building housing at all income levels a priority.” After she voted against State Senator Scott Wiener’s upzoning bill SB 79 in committee, Politico called her “the state senator who could foil the YIMBY agenda.” On June 3, she doubled down and voted against the bill again when it came to the floor of the senate.

Her comments left YIMBYs gobsmacked:

“The state has prioritized development, development, development,” Wahab said. “The types of development that are going up with zero parking and all these giveaways to developers have also not translated to housing that has dignity that people want to stay in and raise their families in.”

The trouble has been building for months. In her very first hearing as head of the housing committee1, she doubted that adding new development would put downward pressure on prices. She’s criticized transit-oriented development, reductions in parking spaces, and taller buildings. At best, Wahab is all over the map. At worst, she’s been a Flat Earther, but for housing.

So, why the heck did we endorse her? And what do we do next?

Organizations that make endorsements can use a few strategies, and it's worth understanding each. They all have costs and benefits.

Strategy 1: Endorsements Are For Purity

Some organizations endorse only The Very Most Aligned, treating their endorsement as a precious resource that should only be given to candidates they stand with 100%. Gold stars only.

The benefit of this is that you're rarely embarrassed by an endorsement. No one is ever going to look at you side-eyed and say “Her?” (Your likelihood of a Mayonegg moment is minimized.)

The cost of this strategy is that — especially when you're beginning to build power and influence — in most elections there isn't going to be a candidate to endorse. Most of the time, in most places, your choice is between “Ok” and “Terrible.” Or even “Bad” and “Worse.”

We're all familiar with this math at the Presidential level, where it gets disparagingly called “purity politics,” (ask your local Green or Libertarian party member how it’s been working out for them). At the national level, it’s easy to see why this is a dead-end. But at the local level, where you might be endorsing in several districts and on several levels of government, it's even more tempting to stay silent (or endorse zero-chance candidates) so that you can claim you are staying “focused” or “saving your powder.”2

Strategy 2: Endorsements Are For Winners

This is a common strategy for organizations that prioritize access above all else. They don’t want to be left out in the cold, so they support whoever they predict will be in power.

A lot of industry groups follow this pattern (though not the ones that invest heavily in lobbying efforts). If you want a few things that are mostly non-controversial, often technical, it can be a valid strategy to cozy up to likely winners and just bank on mutual appreciation to help you get your small asks across the finish line.

On the other hand, for groups seeking bigger structural changes this is a bad strategy. You create zero incentive for change and weaken the power of your endorsement, both with your base and the politicians you’re attempting to sway. Endorsing only the likely winners weakens your brand. Over time, you sacrifice influence for access.

Strategy 3: Endorsements Are Relative

If it’s not clear by now, neither option one or two is what we do. Here’s how we think about it at YIMBY Action.

Voters want to know who is better and who is worse on your issue. When we make endorsements, we are often practicing incrementalism. The best politician on your issue likely isn’t running yet! The issue isn’t popular enough and the parade isn’t big enough — yet.

So the choice is, do you publicly rank marginally better than the people they are running against? This brings us back to Wahab.

When she ran in 2022, Wahab’s endorsement questionnaire responses were a mixed bag, saying things like “If elected, I will pass laws to ensure we make building housing at all income levels a priority,” and “I believe there is a balance to be struck in ensuring due diligence is being paid while expediting the process.” Not great, but not terrible.

By contrast, her opponent told us “I am not interested in being endorsed by a pro-developer organization.” That’s candidate for “fuck off.” There was no doubt who would be worse on our issue.

We knew that Wahab wasn’t great on housing, but we hoped she would be pulled into the orbit of progressive pro-housing voices like Assemblymember Alex Lee and Assemblymember Matt Haney. She wasn’t perfect, but she was better than the alternative.3

When you decline to issue an endorsement because none of the candidates in the race are great, you leave voters without guidance and you fail to build your electoral power in the district. In order to build constituent power, you have to be active in the district, doing the footwork, building the muscle — not sitting on the sidelines.4

Now what?

What do you do when someone you’ve supported in a campaign is actively working against your agenda? What will YIMBY Action do — and what aren’t we doing — as Wahab continues to vote like a NIMBY?

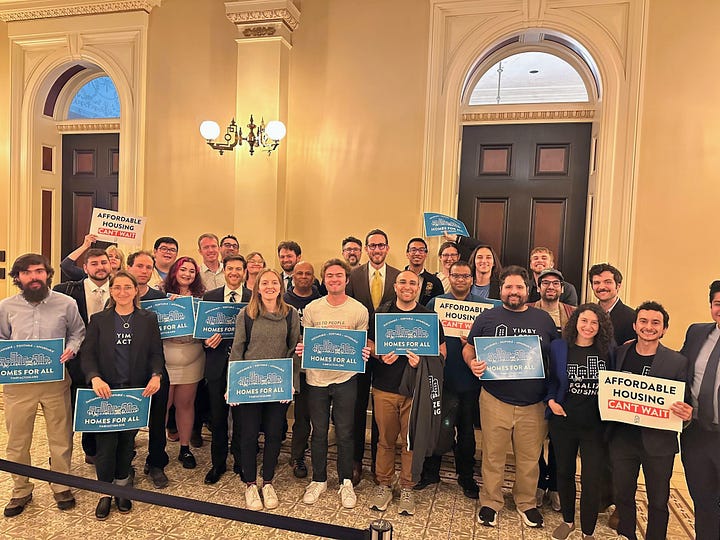

Endorsements are a point in time and a relative grade, not a commitment to ongoing support. When legislators go in the wrong direction, it’s critical to let them know how unhappy you are. YIMBYs are calling her office, and we are calling her out in public (with posts like this one) and in the press. By doing this, we are indicating publicly that her votes will cost her support in future elections and that there is an opening for candidates contemplating challenging her.

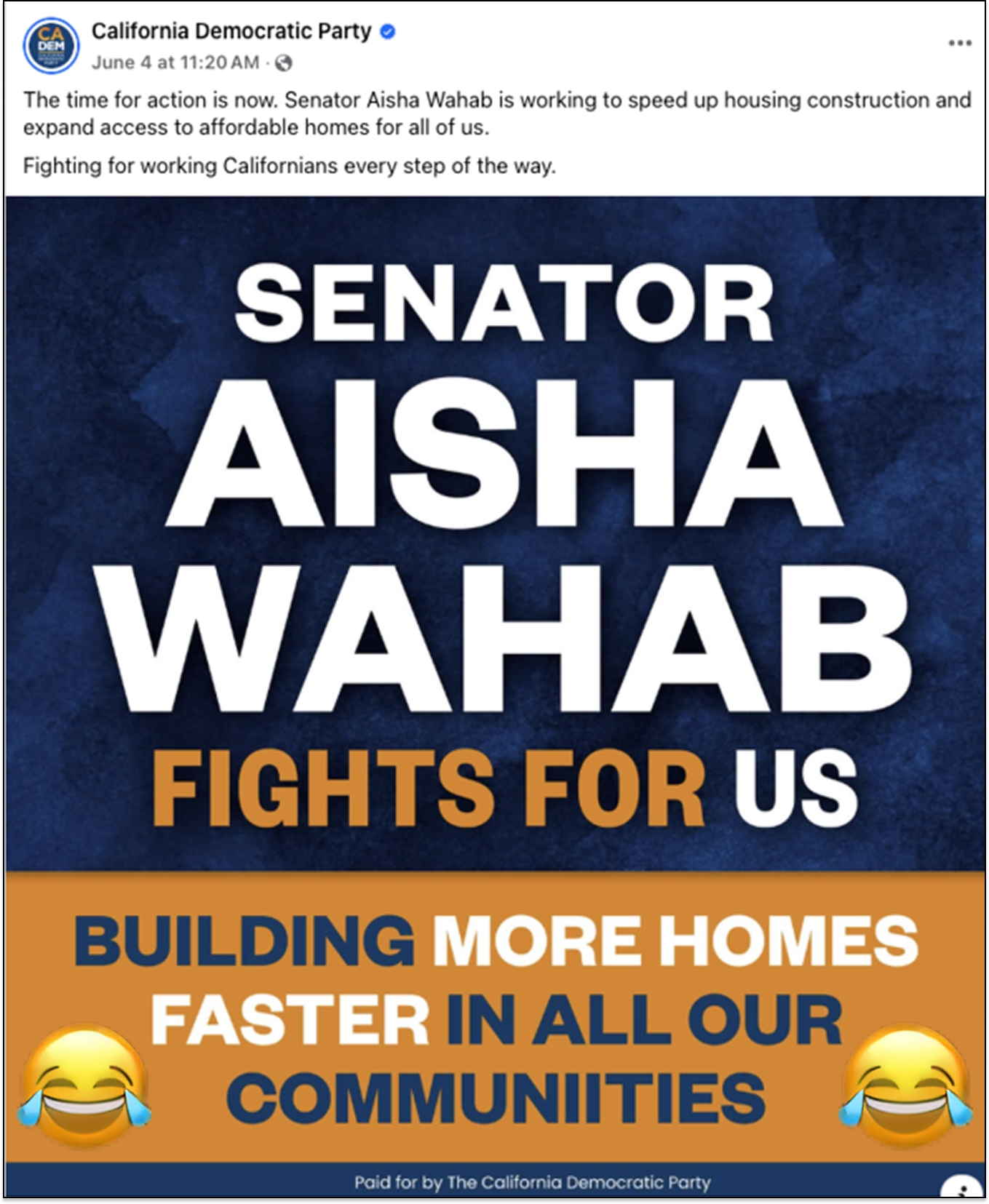

Our chapter is actively growing in her district, which means the pressure mounting for her to rethink her positions will only grow. More members, more allied organizations forming an ever-broader coalition, and more chatter in the press is all about delivering signals that these positions are bad for her political future. She feels the tide is against her, which is why she asked the Democratic party to run Facebook ads in her district claiming she is fighting to “build more homes faster in all our communities” right after she voted to not have homes built faster in communities. She’s feeling the heat, and YIMBYs need to keep the pressure up.

Here’s what we aren’t doing — rescinding our endorsement. (I’ve gotten this question from a few YIMBY Action members.) Why not?

For one, it wouldn’t really mean anything. When we issue an endorsement, we do it for a particular candidate in a particular election. It doesn’t mean we are cosigning everything that person ever does for eternity. We backed Wahab in her 2022 race. That’s it. What would rescinding our endorsement now mean, actually? That we want to re-do the race? That we are extra super-duper mad about her votes?

Here at YIMBY Action we are against pointless grandstanding. When we grandstand, we always have a point.

Worth noting the larger problems that the Senate Leadership would put her as chair of the housing committee.

I know folks are going to push back on this, so I want to reiterate: Why shouldn’t you “save your powder” for other races?

PACs and organizations that mostly just move money around in races might do that, because it’s easy to move money around. You’re generally not trying to build up a local brand, but demonstrate you have a big bag of money you can hit politicians over the head with as-needed.

If you’re attempting to build constituent power and become a go-to brand with voters, building electoral influence is a multi-round game and a muscle you have to build. You have to be visibly in the game, visibly building political weight in order to create the path for better future candidates and incentivize current candidates to cater to you.

Some have argued that progressive pro-housing voices are more dangerous than conservative ones in the current California State Legislature. But by that same token, pro-housing progressives are even more valuable. This kind of 3D chess thinking can cause you to neglect the bread and butter basic politics of constituent power: you need to grow your membership in the district. You have to become a bigger group in the trench coat.

Of course, there are races where all candidates are genuinely equally bad. And in those places, YIMBYs have their work cut out for them: building the base and making the housing shortage a more salient issue in that district. Vocally anti-endorsing candidates is something that should be done rarely, but loudly.

I understand it's a tough problem, but I think you ahould not endorse over very marginal differences if the candidate is net bad on your issue.

One, candidates have no incentive to be better than marginal. Two, people usually decide who to vote for on mutiple dimensions, i.e. are not single-issue voters. Telling people they have two bad candidates on housing is still useful.

Love it! Wish you all the best! A more YIMBY California benefits all residents of America.