Politicians Rarely Lie

Yes, I’m serious.

“Politicians are not defined by their inner lives, but the decisions that they make in public — the ones that actually affect law and policy. Those choices are deeply shaped by the constituencies they depend on and the allies they court.”

It’s the political equivalent of “when someone tells you who they are, believe them.”

People like to say politicians are liars, which definitely feels true. But most of the time most politicians don’t often lie per se. Instead, they deploy strategic ambiguity — ie. making their positions as vague as they can get away with. Their goal is often to make you feel connected and like there are shared values, when in fact they have not committed to anything. Is that a lie?

Candidates resist making policy commitments in public

Campaigns focus on making voters feel a sense of values alignment, while staying as fuzzy as possible on actual policy commitments. Candidates focus (generally correctly) on vibes about who they are as a person, i.e. their personal story, upbringing, community, and values, to evoke a sense of how they’ll govern. Those vibes are interesting, but we know vibes won’t cut it when it comes to actual policymaking.

Behind closed doors, it’s worse. Candidates love to meet with constituents over the kitchen counter and reassure each and every person that they really do see it their way. I’ve had countless conversations with candidates who wanted to “reassure” me that, while they aren’t “shouting” publicly about being pro-housing, they are very pro-housing “in their hearts.” They lean in, hand on your shoulder, and say “I’m with you. We have a terrible housing shortage.”

But then they won’t put it on their goddamn campaign website. They try, nicely, to explain that they need to keep their positions on housing “quiet” until after the election, at which time they’ll gladly do the right thing and support housing proposals.

I do believe that the politicians trying to give me these private reassurances are pro-housing “in their hearts.” I just don’t agree that that’s worth anything. Because voting on legislation doesn’t take place in the heart — it takes place in the public eye. At the end of the day, these private reassurances are worth the imaginary paper they’re deliberately not written on.

If a politician won’t say their position in public, they won’t vote for it in public either. Fundamentally, the compromises that you make while you run for office remain in effect throughout the legislative session.1

To be generous, the politicians who say they want to be bolder are often the first to jump when advocates do the work to make their positions more politically viable. Therefore it’s incumbent for advocacy organizations to make those positions politically viable.

While housing is popular actually, candidates for state and local offices are always acutely aware of housing skeptics in their district. Candidates know exactly which voters in their district will be pissed off by a pro-housing message. Stating publicly “I believe building more housing will benefit this community,” is always going to cost them some votes, so YIMBYs have to actively work to prove we’re worth it.

Public Commitments on Policy are Valuable

A lot of what a politician does is try to collect as many interest groups as they can. Ideally, they want the support of the chamber of commerce AND the teachers union AND the homeowners association AND environmentalists… Candidates run around town having one-on-ones with the leaders of local organizations, collecting supporters like pokemon cards. Robert Dahl’s theory of interest-group pluralism basically summarizes this as “politicians are like several interest groups jammed together in a trench coat.”

But here’s the problem: groups have differing, and often opposed, agendas. Especially for groups fighting for the level of change YIMBYs envision, our goals are incompatible with other interest groups a politician might want in their trench coat.

As an advocacy organization fighting for major policy changes, our job is to be (1) valuable enough that we can (2) demand public specificity so a candidate is willing to (3) give up other interest groups to have us inside their trench coat coalition and (4) still win.

This is where the game-theory gets complicated. How much influence in the district does YIMBY have? How many people will we mobilize to canvas? How many people will throw a house party? What’s an endorsement email worth? As candidates eyeball the size of our voting bloc, they are inevitably comparing us to the ones they are giving up. There is a direct relationship between how much electoral power we demonstrate and how bold they are willing to get in their commitments. With multiple candidates trying to find their “lane” (aka grouping of interest groups) getting commitments from candidates becomes an elaborate dance.

Ultimately, YIMBYs want our candidates to win, and to celebrate YIMBY as part of their coalition. (See Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss or CA Senator Scott Wiener for details.) We want them to make as many binding commitments for that support as possible.2 Given the size of our support, what’s the reasonable maximum amount of specificity we can get from a candidate?

We don’t want sweet words in our DMs. We want politicians to hard launch us on their Instagram. But we’ve got to be worth it.

“If you’re nodding along in agreement at this point, your next question might, “but how does that work in practice?”

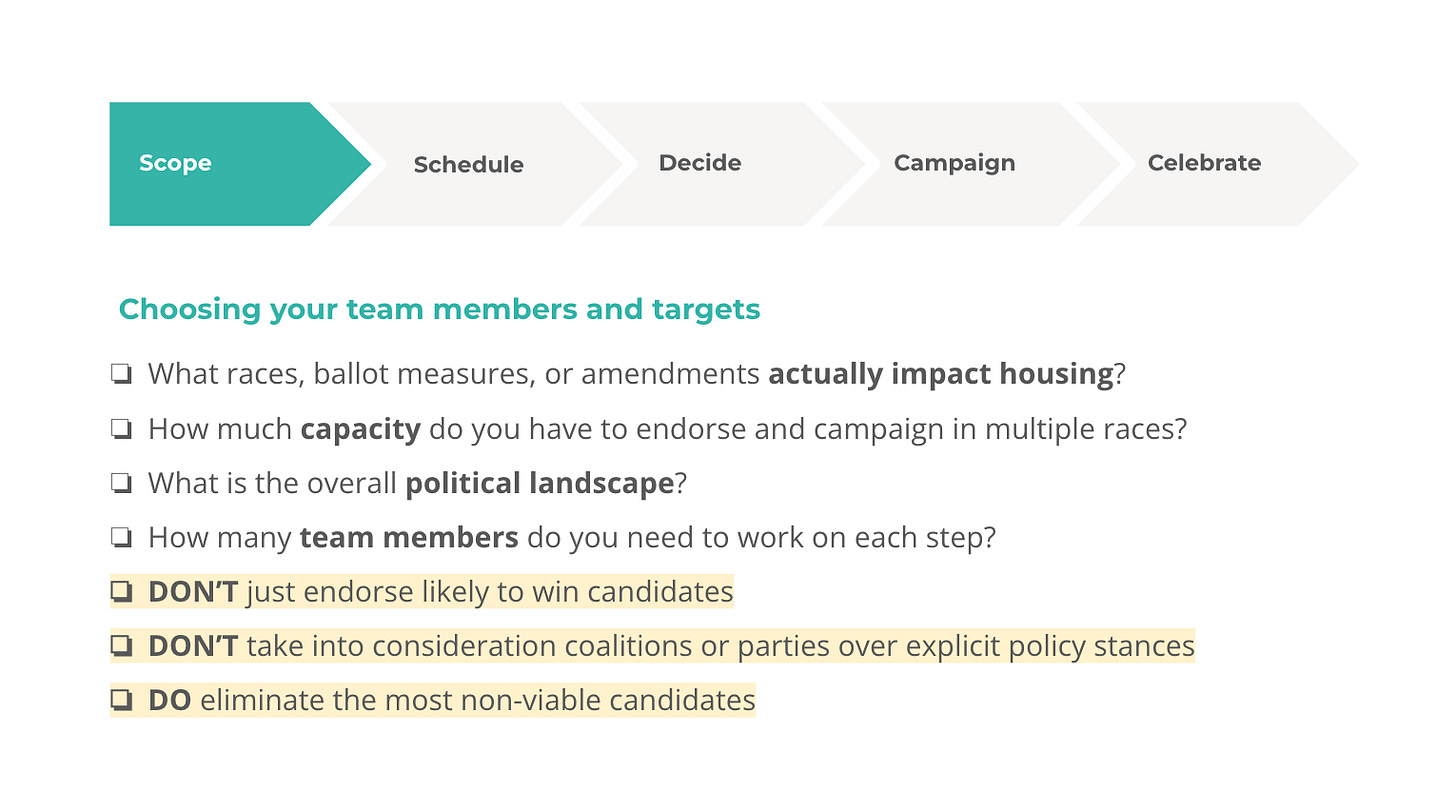

For organizations that want to build their Electoral Power, there are a few key considerations to maximize the impact of your endorsement process. When a Yimby Action chapter endorses, they’re pursuing the following goals:

Demonstrate the value of the YIMBY voting bloc

Educate politicians about the policies so that they can get specific

Collect specific and public commitments from candidates

Candidate interviews, debates, and questionnaires are all tools that we use to advance all three goals at once.

Chapters that are effectively building local power have visible leadership that candidates frequently want to meet with. The bigger your group, the more often potential candidates reach out to get a coffee and discuss their candidacy in advance. A cynic would say they’re looking for the path of support without commitments, but it’s a great opportunity for chapter leaders to guide candidates on the path to (reasonable) public commitments, while demonstrating the value of YIMBYs in their district.

For example, I had coffee with a candidate for a city council this week and he asked me, “What can I do to show YIMBYs I am a great candidate?” I said, “You should write an op-ed about your personal housing story and why you believe the proposed rezoning initiative is the right path for your city.” He was noncommittal, saying “Hm, I’ll think about that.” This is a perfect case of a candidate who is in the middle of their decision-making process about which interest groups he wants in his trench coat and how badly.

A good endorsement process forces those decisions while incentivizing the right ones.

The capstone on public and specific commitments is the candidate questionnaire. Many groups don’t publish their questionnaires, but I think that encourages candidates to mislead about how far their willing to go. Better to get a more tepid answer to a questionnaire than to get bamboozled into thinking a candidate will be more aggressive than they actually will be.

Chapters start with our basic template questionnaire. Not too short, not too long. These get customized depending on what the most important issues are and an assessment of what reasonable commitments a chapter thinks they can get locally. Developing local questionnaires help chapters think through policy priorities, assess where the Overton window is, and make their best guess about where they can pin candidates down.

A good questionnaire is an open-book test — candidates should reach out to members and say, I got this questionnaire, and what are the right answers? It’s not a gotcha: We will tell them.

A great endorsement process gets candidates fighting for your support and gets your base excited to mobilize for a candidate. There are several ways to structure candidate interviews or debates, but the overall goal is to create a positive feedback loop where a candidate goes bigger on their commitments because they can literally see the potential voters right in front of them.

Candidates want to be all things to all people. Advocacy organizations have to incentivize them to abandon that strategy. Of course it get’s complicated, but that’s the basic incentive model: We show candidates that pro-housing politicians win elections.

A great endorsement process also feeds directly into a mobilization strategy. A candidate gets the base excited to celebrate their endorsement with volunteer phone banks and member-hosted house parties. We show them how much easier it will be for them to win their next election with our endorsement and our volunteers. We say to them — the more we can help you, the easier your life will be, and the more you support housing, the more we’ll support you.

We show them, in essence, that it is in their interest to have us inside their trench coats, even if it means losing a NIMBY or two.

This isn’t to say that you can’t change that math during the legislative session. Elections are a crucible through which politicians speed-run these decisions and bake in their assessment of their personal coalition. If you don’t get in during election season, it’s harder to get in during legislative season. During the legislative session, there are other lobbying strategies for changing a politician's mental math on voting for reform, top of mind being citizen lobbying (activating people in the district to contact their legislator) and coalition lobbying (getting existing groups with existing power to lend their support to your effort for a shared priority). More on these in later posts.

Over time, you build your parade and demonstrate its value. By building electeds a parade, and letting them march at the front of it. It’s ok for that parade to be small at first — the point is to throw a bigger one the next time. The bigger your parade, the more specificity you can inspire.

This is a great piece! Very helpful. I’ve gotten to know candidates who have them become elected officials, but this is a better way to think of how to approach them. Get them on the record with public statements, get them to put housing as the first issue on their website, publish the questionnaires of our endorsements, treat the endorsement questionnaire as an open book test… great points!