How We Forced the “Richest Retirement Town in the Country” to Approve More Housing

A YIMBY Law story

Hi, it's Laura. I’m excited to have YIMBY Law Executive Director Sonja Trauss tell this story right after our Strong Towns post. Her experience is part of why I think strong state laws and enforcement are necessary for housing abundance.

Rancho Palos Verdes city councilperson Barbara Ferraro was caught in a vice. "I mean it's really onerous,” she said. And what was worse, was only one way out — a way that she didn’t want to take. But, she went on to say, she didn’t have any other options. “It's not something that we can go back to. We don't dare right now," she said

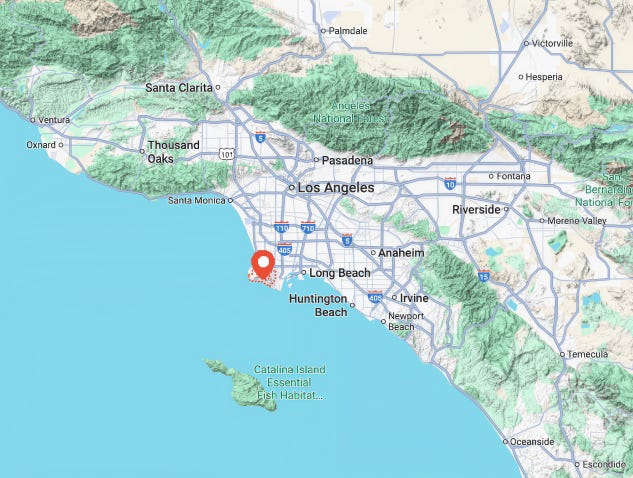

What she was referring to was a recent controversy in the Southern California city that according to at least one blog, “is known for its breathtaking ocean views, luxurious homes, and serene environment, AND has been named the richest retirement town in the country.” The problem was this: The city government was under pressure from local NIMBYs to block the construction of a new apartment building. Many of the elected officials wanted to give in to them, but there was one big problem. Thanks to California’s laws and the work of groups like YIMBY Action and YIMBY Law to enforce them, they couldn’t. In fact, the city was caught in a trap — one way or another, it was going to have to allow new construction.

Here’s how it all unfolded.

Like every other municipality in California, Rancho Palos Verdes has to prepare a “housing element” every eight years, which spells out the places it will allow new housing to be built and maps how it plans to achieve it. It did, and the state certified that plan. So far so good. As part of its housing element the city identified sites where it would allow 647 new units of housing, a plan that would require upzoning several low density parcels for multifamily buildings.

But when a developer purchased one of those parcels and submitted an application to build housing there, some neighbors freaked out. Housing element plans aren’t supposed to be real, after all!1

NIMBYs lobbied the city council to not only stop that project, but also to reverse the upzoning of several other sites. Bowing initially, the city council decided to remove three specific sites from its state-certified site inventory, including the one with a housing proposal on it. City staff prepared a revised draft housing element reflecting these removals and submitted it to the state’s department of Housing and Community Development for formal review, and HCD (appallingly) agreed to allow the city to remove these sites. In years past, that would have been the end of it. A bunch of NIMBYs would have steamrolled the city council and HCD would have looked the other way, reverting to the toothless inaction that characterized the department before we forced it to do more than just rubber stamp local plans, no matter how bad they were.

But not so fast.

Because of YIMBY Law's reputation for taking swift action to enforce housing laws, the developer's attorney reached out to tell us about how the city was planning to kill his client's project, and asked if we could help. We could and we did. Because neither the NIMBYs nor the city council nor HCD make the final decisions on zoning questions like this one. Nor do we. The courts do.

On March 17, before the first city council hearing on removing the sites from their list of suitable housing development sites and rolling back the previous upzoning, we sent a letter telling them they couldn’t remove the sites or roll back the upzoning. That seems to have scared them. They postponed the vote, and met again to consider it on June 3. We didn’t let up. Before the second meeting, we wrote them again, reminding them that removing these sites could invalidate their housing element and raise the possibility of the builders’ remedy, a provision in state law that allows developers to bypass local zoning and other requirements when a city fails to follow its obligations. All told, the two letters took us a couple hours of time to research and write — but drew on years of work to back them up.

Our goal was to box the city council in. We told them they either had to approve the upzoning or face the builders’ remedy. Either way, housing was going to get built. We wanted them to realize that the housing was inevitable.

And the city officials knew that. All of Rancho Palo Verdes’ options involved building more housing — SB 9, builders' remedy, and housing element upzoning. Each reform closed off a choice the city might have made to deny housing. This isn’t by accident. For years, YIMBY Action and YIMBY Law have worked together with CA YIMBY and other pro-housing groups in California to pass laws to get more housing built.

Another part of our work is to help implement those laws. Thanks to California’s third-party right of enforcement, YIMBY Law can take NIMBYs to court when they fail to live up to their legal obligations. In other words, over time, we have crafted laws that prevent NIMBYs in local governments from blocking housing — and have built the legal capacity to enforce those laws. Checkmate.

The only option they had was, as the city attorney said, to keep the sites on their site inventory and let the application for housing proceed..

“The exposure to builder's remedy is not something to be taken lightly,” said the city attorney of Rancho Palos Verdes during the June 3rd meeting, adding that the southern California city was involved in four lawsuits already.

Councilmember Sharon Yarbor agreed that she wanted to avoid the builders' remedy at all costs. "There is a possibility,” she said, “and I don't know how great or small that possibility is — that there could be a determination that because we are [attempting to stop processing the housing application, we would be violating] in some way some provisions — and God knows there's a lot of them in the housing act — putting us at jeopardy for builders’ remedy. That to me is a hill I would die on — I do not want there to be a scintilla of risk of reopening the door. And I'd like assurance from the council, from the city attorney, and the city staff, that there is no way on god’s green earth that if we do this, that builders’ remedy could come back to bite us on the butt. That is the worst thing that could happen, worse than having this project [..] I don’t know if you can assuage those concerns.”

Mayor John Cruikshank could not assuage those concerns: “I'll ask the city attorney to opine but my guess is that we can't assuage anybody's concern of any current or future legal action based on what we do tonight." The city attorney chimed in to say, "Amen. True. True."

"So unfortunately I mean we are in a very difficult position," continued the mayor, "The city's in a really bad position in terms of finances right now [...] We can't afford in the next couple months and next year to pay out [...] to try to settle lawsuits that we get from God-knows-who [...] about some housing element approval that we did not do or we took out from zoning. That's just the reality of it. And we're going to get hit with those applications and those lawsuits. It's just inevitable if we pull it out."

In the end, those letters worked. The city council voted not to risk it, keeping all of the sites on its inventory. Thanks to years of political organizing and legal work, cities like Rancho Palos Verdes are stuck. They may not want to approve new housing, but they don’t have a choice.

It’s just inevitable. That’s just what we wanted to hear. One by one, we blocked all of the NIMBY escape routes.

Despite many people making public comments urging the city council to fight, in the end, the city made the right choice. (It really didn’t have any other choice.) The city council voted 5-0 to keep all of the sites zoned for multifamily housing. Either they had to follow the law, or run the almost-certain risk of facing a costly lawsuit.

Without third-party enforcement by organizations like YIMBY Law, California Housing Defense Fund, Californians for Homeownership, and other pro-housing legal outfits, this story would have ended very differently. Cities are accustomed to bullying developers into not asserting their rights. Many state agencies are loath to crack down on local governments, since they have limited resources and know that enforcement can be a time-consuming game of Whac-a-mole with recalcitrant local governments.

Laws only exist if everyone believes they do. So that’s why YIMBYs work on implementation from many different angles. Sometimes that means making sure that State Attorney General Rob Bonta gets lots of positive press for his actions when he enforces state housing law. Sometimes it means encouraging the Governor to instruct his departments to take strong stances. And sometimes it means making things inevitable.

You may be thinking this freak out doesn’t make much sense. After all, the whole point of the housing element is for cities to make lists of places on which housing can be built. If housing actually gets built on those sites, that seems like the point. But without a court willing to enforce the law, many cities believe that these plans are a negotiation rather than an obligation.

Really amazing work, progress the entire housing movement depends upon. To hear a council member say they will die on the hill for housing to preserve their ability to avoid even more housing—bittersweet music, but mostly sweet

I wonder how cities would be responding to these laws if they were as flush now as they were in the 2010s. It’s weird to see how the combination of an uncertain economy + uncertain federal funding + longterm infrastructure debt piling up makes cities much more likely to comply with basic laws to avoid the consequences

Wonderful story. Thanks for sharing it. Inspiring us down in OC.