Strong Towns Need Strong States

An open letter to Chuck Marohn

Editors note: You might also want to check out Chuck Marohn’s reply to this on the Strong Towns website and Addison Del Mastro’s ruminations on the discourse on their substack.

For those not sufficiently deep in The Housing Discourse,™ Chuck Marohn is the author of Escaping the Housing Trap and founder of an often YIMBY-aligned group called Strong Towns. He says he agrees with YIMBYs on ninety to ninety-five percent of everything. But because the differences are what seem to come up most, let’s talk about some of that pesky five to ten percent today.

YIMBY Action chapters across the country frequently work in coalition with both Strong Towns local groups and other pro-housing folks on rezoning campaigns, single-stair reform, and other pro-housing policies. YIMBY Action chapter leads have gone to the Strong Towns conference, and visa versa, so there’s significant overlap.

But there’s also sometimes a gap that folks don’t understand. Why does Marohn appear so YIMBY-skeptical online? And how can we understand one another across that gap? To be clear, it's not just Marohn: many otherwise pro-housing groups get nervous about the idea of strong state legislation crashing down on local cities. But he is one of the more vocal people articulating this concern.

For example, in May, Marohn critiqued Ezra Klein’s and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance for what he saw as its top-down, technocratic hubris: “Abundance is a mirror image of Escaping the Housing Trap,” he said. “Where the former sees dysfunction as something to be unlocked with smarter governance, the latter sees fragility as something to be understood and respected.”

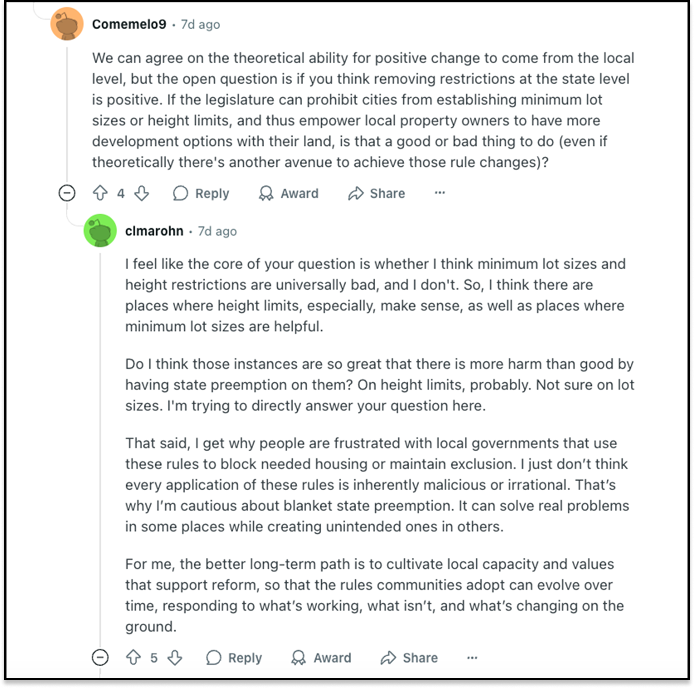

On r/StrongTowns, Marohn got more specific on housing policy, getting into a back and forth in which he defended the ability of local governments to set their own zoning rules and argued against state preemption laws that limit or take away that capacity.

Marohn is giving voice to an interesting part of the pro-housing ecosystem: folks who are pro-housing BUT also believe deeply in local control. In the above thread, he makes the case for local control by focusing on three ideas:

State level preemption risks running into knowledge problems, as for example, when a policymaker far away from a local jurisdiction makes a rule that doesn’t take into account local conditions.

Reforms should begin and end at the local level.

State governments ought not to try to override those regulations.

In practice, most fights over housing legislation in statehouses across the country center on this question of Local Control vs State Leadership. Traditionalists argue that housing regulation, and land use in general, has been the purview of local governments for decades, and there is no justification for state governments to intercede. YIMBYs, obviously, disagree.

So, let’s get into it.

Starting with the obvious, Marohn isn’t making up the knowledge problem. A bureaucrat in D.C. probably shouldn’t be deciding how far apart to space the street lights in San José, San Juan, or Sandusky. Some amount of localism is important for functional communities.

Further, Marohn and Strong Towns believe that we can correct a city’s doom loop with education and local activism. And, to be fair, they do a really good job showing how chronic housing shortages hurt the very communities defending anti-housing policy.1

Where YIMBYs pull away from the local-control crowd is that we see the housing shortage as a massive collective action problem. While Strong Towns focuses on education and local consensus-building, YIMBYs believe that state intervention is a necessary part of the remedy.

We argue that the question centers around externalities: How much are the costs of NIMBYism felt locally and therefore possible to rectify locally? Do cities suffer enough when they shoot themselves in the foot with anti-housing policies such that education is an effective enough tool to stem the bleeding?

YIMBYs… well, we’ve watched a lot of cities just keep shooting themselves in the foot. The incentives for wealthy communities to hoard resources are extremely hard to combat. The structural problem is that negative effects are felt most by non-local voters, and the fact that local governments are deeply biased in favor of neighborhood defenders. Education alone is insufficient.

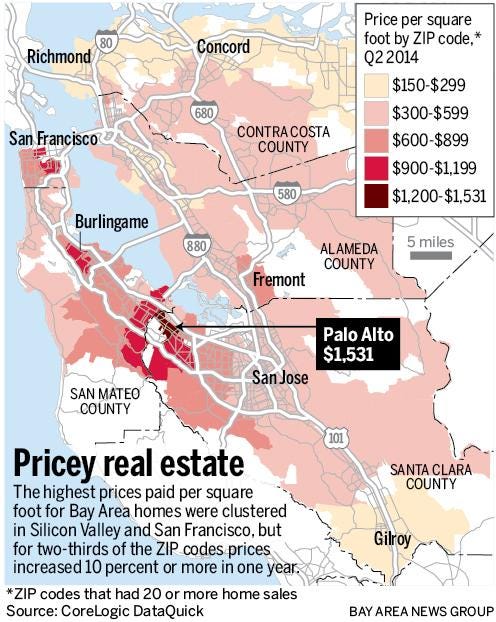

The most notorious example of this regional race to the bottom is the Bay Area. For decades, every city in the region added jobs (with great tax revenue) and very little housing. We even ended up with the former mayor of Palo Alto infamously complaining that other cities weren’t absorbing Palo Alto’s job growth, and that the solution was to just stop the job growth.

You know things have gone seriously awry when killing jobs is the proposed solution.

Marohn believes you have to solve problems at the level of government where tradeoffs can be accurately assessed. YIMBYs agree — and that means working at the state level. Only there can chronic problems like workforce housing shortages or mega-commuting be accurately assessed and command the attention of legislators. Only at the state level does a chronic teacher shortage or an aging population become an unignorable symptom of a housing shortage.

As a result, most YIMBYs believe state legislation is necessary for any permanent solution to the housing shortage because the externalities of anti-housing policies have the triple-wammy problem of:

being in the future,

being diffused across an entire region,

disproportionately impacting younger people, lower income people, renters, and all the folks who don’t know who their city council members are.

In his Reddit comment, Marohn wrote that, “the better long term path is to cultivate local capacity and values that support reform, so that the [local] rules communities adopt can evolve over time, responding to what’s working, what isn’t, and what’s changing on the ground.”

But the problem with this position is that in many cases the American regime of local land use is working as designed. The people writing the rules at the local level believe these rules benefit them — because they do. These advocates pulled decision-making down to the level of government where they had the home field advantage. It may sound like a tautology, but local control gives control to the folks who are most active locally, which means prolific Nextdoor power users, if you know what we mean.

In other words, zoning was created just as much to keep white and Black people from mixing as it was to keep industry and residences from mixing. “We need to preserve the character of our neighborhoods, by which I mean prevent immigrants and people of modest means from buying or renting near where I live,” as McSweeney’s once ventriloquized. It's impossible to overstate how racist, classist, and xenophobic the architects of American land use were; and how racist, classist, and xenophobic its impacts continue to be.2 The point was to hoard resources, especially high-quality public schools, and it worked.

The avalanche of the housing shortage is falling on us all. But it still serves the interests of some portion of every community in each and every city across the U.S. You might think it’s the Homevoter Hypothesis, but it’s honestly a lot more banal. Many older Americans benefited from previous economic expansions, were able to secure housing in prime areas before things became too expensive, and are happy to keep things the way they are.

Local playing fields are tilted one way — against solving the housing shortage. Pro-housing coalitions are winning numerous local battles for more inclusive zoning and permitting policies, but no amount of local pro-housing activism is going to change the incentives in Beverly Hills. Or most places that end in “hills.” Economic integration, where people who work in a community can live in a community as well, is not everybody’s goal.

While there’s plenty to debate, fundamentally there are many places where we agree with Marohn. The most important one is this: Local governments have a lot of power. If they want, they can stymie pro-housing legislation really badly. That means that all the members of the pro-housing movement — YIMBYs and Strong Townies and everyone else — need to make sure our ideas are popular in both our towns and in our states.

Strong Towns produces excellent content showing how anti-housing policies drive up prices, stunt economic prosperity, and hurt local communities. They focus on helping local officials, planners, and advocates understand that their wounds are self-inflicted, and they emphasize giving communities the tools they need to stop shooting themselves in the foot.

For more, see books like The Color of Law, Stuck, or The Warmth of Other Suns.

Well said. To lean into the Strong Towns parlance, we all want to restore bottom up community planning. Which means restoring agency over residential land use to the lowest level of decision-making possible, the individual property owner

State legislation that helps restore decision-making to the individual landowner isn’t the same as state-driven highway planning or other top down policies, it’s a fundamental part of reviving true bottom-up planning. State-level advocacy doesn’t replace the local organizing, it’s a complement

Thanks for writing this, it's really good!