The Solutions To The Housing Shortage Are Often Not Popular.

Don’t panic.

Abundance is a hot topic right now. Elected officials are trying to figure out how to capitalize on the moment, launching a new federal abundance-oriented Congressional Build America Caucus.

But a recent private poll by a Democratic firm about efforts to increase housing in the United States concluded that federal YIMBY policies not popular:

“Despite the housing affordability crisis, federal zoning reform, density mandates, and ‘YIMBY’ preemption policies generally poll below 50%. Support is especially low for preempting local control (e.g., federal density mandates at 48.2% and NIMBY overrides at 48.3%), indicating a wariness of federal overreach and a resonance of Republican arguments that these policy decisions should remain at the local level.”

Here’s the paradox: most policies get less popular the more complex they appear. Housing is popular, actually — but ideas like reforming floor-to-area ratios are not, because what the fuck even is that?1 There is a confusion penalty — the more complex a question is, the more people will vote no. (This is the politics version of a common issue in tech. Don’t ask your customer for their solution, ask them for their problem.)

Housing policy is rife with impenetrable jargon: ADUs, LIHTC financing, and AMIs are just the tip of the iceberg of planner-speak. Part of the reason that pro-housing forces have been losing for decades, is that NIMBYs and well-meaning bureaucrats talk in complex, hyper-localized, technical language, making their decisions impenetrable to average citizens — and the costs invisible.

By contrast, every victory YIMBYs have achieved has in part been due to a relentless human-ification of policy. It’s why our members put down the charts and give public comments based on values and social goals. And it shows up in polling data over and over.

My favorite poll from Pew does a great job of, for example, making “Transit Oriented Development Policies” clear to an average voter:

But as everyone knows, how you ask the question has HUGE impacts on what kinds of responses you get. And when you drill down into what are the causes of high housing costs and what are the policy solutions, it’s a hot mess. Voters think high housing costs are bad, but they don’t always ascribe those costs to restrictive policies.

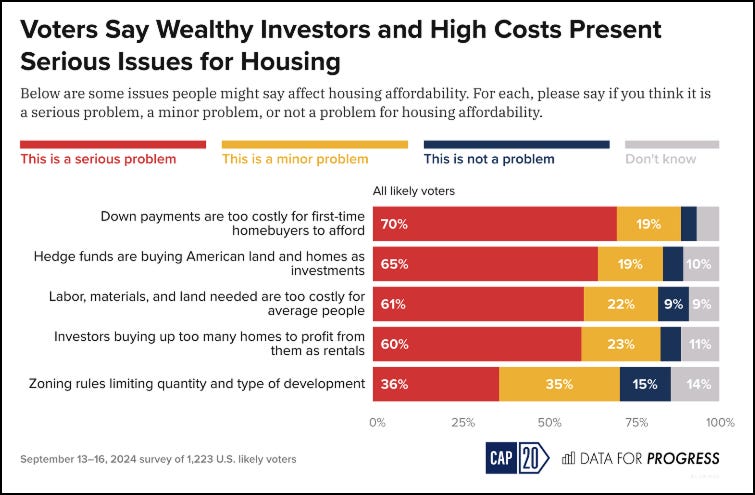

Here’s a poll from Data for Progress that shows just that:

That messy interaction between knowing something is a problem but not being sure what should be done about it (and by whom) shows up in that recent polling, which showed middling support for federal policies that might boost housing production.

Single-stair reform is a great example. This polling showed it below 50% popularity2 — but we’ve been a part of several successful single-stair reform coalitions and cities across the country are getting excited about this wonky-but-high-impact reform.

This is ok! This is how a representative democracy is supposed to work. But for it to work, it requires effective, strategic organizations channeling values into effective, strategic advocacy. The job of the advocacy organization is to bridge complex conversations with elected officials, while mobilizing and inspiring values-oriented with voters. YIMBYs have learned how to hammer on the values, drawing the line between goals and policies with lawmakers.

In other words, single-stair reform may not be that popular. But bringing down housing costs is.

To put a bow on it:

Average voters grade politicians on outcomes, not on methods. People hate how expensive housing is right now. They desperately want their elected officials to do something about it.

Our job as YIMBYs is to be the glue between effective policy and the elected officials; to show politicians that voters will reward them for implementing pro-production policies.

Without YIMBY, it’s easy for politicians to focus on popular-sounding-but-ineffective policies that won’t solve people’s problems.

What happens in the absence of effective advocacy? We see this all the time. People tell pollsters they are riled up about Blackstone buying houses, so even though there’s little evidence banning corporations from buying homes will improve affordability, politicians focus on Blackstone Bans instead of apartment bans.3

This is a constant challenge for anyone trying to do policy work, whether in housing or almost anything else. Stuff gets extremely wonky extremely fast. People are easily confused, frustrated and dissuaded from participating in complicated land use nonsense.

The difference between elected officials and everyday people means we have to be adept at shifting how we talk. As lobbyists, we have to know the technical details and explain why specific policies will be high-impact.

But as organizers, our job is to inspire people to join the cause based on values — not bludgeon them with overly-detailed arcana about minimum stair requirements, maximum parking requirements, set-backs, lot sizes, and so on.

That’s why our t-shirts say “Legalize Housing,” and not “Incentivize Elected Officials At The State and Local Level to Reform Various Zoning Regulations That Constrict the Supply of Housing at Equilibrium Levels Lower Than They Would Otherwise Be.”

And it’s worth asking how much of land use policy was deliberately made complex in order to make it an obscure impenetrable morass, unless you discover the mythical zoning amulet.

Worth noting that Federal Single Stair reform seems to poll with much greater popularity than I would have expected! The way this question is asked, folks might have concerns about federal incentive programs or any number of complex issues that are impossible to pick out. And yet 49.2% of people said yes!

Please don't send me articles about why you’re mad that Blackstone is buying houses in the suburbs.

I feel that your post makes great points, and details well how policy and politics have become so disconnected and great communication is needed to reconnect them. It’s frustrating that people (myself included) often settle on policies that have strong narratives even when they are proven to not solve issues. I think this is the biggest hurdle for the Abundance movement. We are having to retell the story of issues and popularize our account over ingrained ones. Sometimes the facts alone convince people, but most of the time a simple, relevant, and engaging plot is what wins over people.

This is great. I have been tracking a zoning reform in the Pittsburgh region and seeing that advocates have been making gains when they show the exact changes (as in, measuring existing vs proposed setbacks) and taking pictures of the difference. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words, especially when it comes to complex policies.