More Principles for Achieving Abundance

Key concepts Abundance should borrow from YIMBYism (Part 2)

You can check out Part 1 here.

4) Barriers to Entry Are Huge Drags on Growth

The literature on barriers to entry and the drag it puts on the economy is vast. And society should probably do something with all that useful information.

Instead, elected officials are constantly writing laws that create new and elaborate barriers to entry for everything from electric scooters to new homes. Barriers to entry range from outright limits on the number of firms (like limiting food truck permits in New York) to creating elaborate occupational permitting that drives up costs.

And existing firms love finding ways to keep new competitors out of their markets. Whether it’s bars arguing the market is oversaturated or a home owner arguing that parking spots will be gobbled up by new residents, there’s always a reason to pull up the drawbridge and get your government to help you keep others out. After all, competition is disruptive and noisy and full of new people who aren’t even an identifiable constituency anyhow.

Oligopolies may be good for the oligarchs, as Peter Thiel often points out, but they’re not very good for consumers. You can argue that the entire concept of restrictive zoning is just one elaborate barrier to entry, creating artificial scarcity that makes current owners wealthier.

Ironically, barriers to entry create the very thing NIMBYs say they hate: Sophisticated Large Developers with Deep Pockets. Instead of mass-producing cheap, low-margin, missing-middle homes, high barriers to entry ensure only large firms can be successful. They have to acquire talent in '“who knows a city council member” and “how to host a public meeting without it turning into a shouting match.” Most developers have to hire PR firms and consultants whose only expertise is community engagement and knowing a guy.

The basic point is this: Barriers to entry drive down competition and drive up prices for consumers. If you’re going to create a barrier to entry, there better be a damn good reason.

5) Participation Is Costly

In 10 years of YIMBY activism, I’ve been to a lot of community meetings, planning commission hearings, and other public hearings. I’ve given and heard a lot of public comments. I’ve used the system and taught others how to use the system to have a pretty dramatic impact on decision-making in communities across the country. And generally speaking, it’s fucking ridiculous.

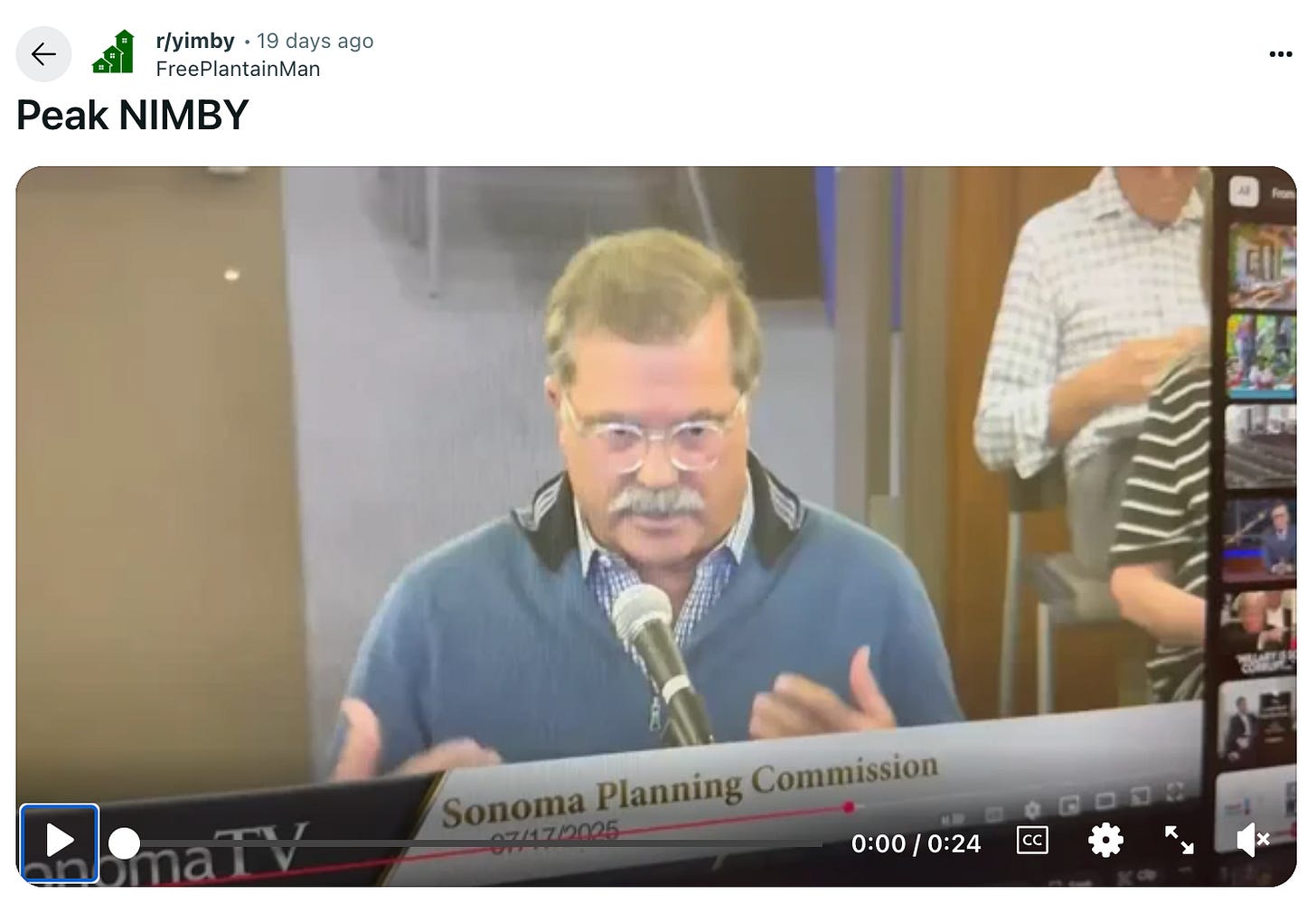

Today in high-opportunity communities across the country, a handful of motivated residents are calling themselves “the community” and showing up to an obscure hearing to influence critical decisions about the future of their region. Working people, people with family obligations, young people, and anyone who just vaguely wants things to function is generally not at that meeting.

We know that the current style of community input is biased in every way. Community input processes are frequently dominated by the most well-heeled among us.

Highly participatory processes reinforce status hierarchies, privileging those who are able to take time from their lives to attend random meetings at 2 pm on a Tuesday. With that imbalance, wealthy people who feel particularly damaged will always be louder than working people who may not even realize the long-term damage being done.

The classic “solution” to this problem is to have even more meetings, even more opportunities for appeal, and even more notifications. But you can’t solve a cowbell problem with more cowbell. Reducing bias in input matters much more than increasing its quantity. More of the same structure of waiting to give a two minute public comment does not result in a less biased sample of local opinions.

So, what’s the alternative?

The first is recognizing we should have participatory meetings about policies, not projects. We need to engage the public when we’re talking about the law in general, not when we’re deciding if it applies in a specific case. When decisions are made by an entire city, an entire region, or an entire state, they shouldn't then get unmade by biased neighborhood vetoes.

The second is to prioritize broad public opinion with polling, focus groups, and contextualized input. Abundance policymakers have to recognize that there are frequently large groups of people who do not show up, but do vote and will reward policies that embrace growth.

I care about community voices, but the proof is in the pudding. And the pudding is currently rich, motivated neighbors hijacking our government to pull up the ladder of opportunity. A politics of abundance must be a politics of representative democracy. We should elect politicians who tell us broadly what they want to do and then give them the latitude to actually do it.

6) Everything has Tradeoffs

The number one antidote to everything-bagel liberalism is to be honest about tradeoffs. As Governor Jerry Brown loved to say “too many goods made a bad.”

All politicians (even Jerry) like to pretend their policies can be accomplished for free. But there is not a single policy change on God’s green earth that doesn’t have some kind of tradeoff. Abundance-minded policymakers have to be vigilant about those tradeoffs.

Unfunded mandates feel great! They’re free to legislators, seem to push costs onto corporations, and they create the sense we’re moving society towards great outcomes. A recent example in the SF Examiner highlighted that “San Francisco is pushing ahead with rules intended to hasten The City’s transition to an all-electric building stock, including its homes.” Sounds innocuous enough, but “‘Rehabs will be delayed,’ said Lajuan Ramsey of Mission Housing, a nonprofit developer. ‘The habitability of units will decline. Occupancy rates will drop, and the property performance will fall as well.’” Yikes!

Abundance-minded policymakers have to be transparent about the costs of tradeoffs, even when they’re willing to pay it. What’s the cost of requiring duplexes to pass elaborate owner-occupancy tests? What’s the cost of making projects using union labor? Passing legislation that is hamstrung with ten goals increases the odds not that you’ll get half a loaf, but instead that you’ll get no loaf at all.

The tradeoff politicians are most inclined to underweight are costs that fall on future residents. And that creates the tragedy we are living with today. Tomorrow always comes, and the point of creating abundance policies is to build a future of possibility. Because I believe that children are our future. House them well and let them lead the way.

I’m not sure that people not attending meetings are dramatically more yimby than those attending meetings. I but there is some of that, but if only those people were nimbys politicians would pick up the $100 bill on the sidewalk.

Your average working class person may want cheaper housing in a vacuum, but he would likely complain about traffic, having more “affordable units”, and using unionized tradesmen too.

The big reason for nimby-ism is that zoning is how you keep the dysfunctional out. That desire exists up and down the class spectrum. Addressing dysfunction would go a long way, but that means doing politics.